Kurt Vonnegut: The Exit Interview

Jason Yoder/NUVO

This interview with Kurt Vonnegut took place last February. At the time, we were both looking forward to his visit to Indianapolis at the end of April for the citywide celebration in his honor. About an hour after we finished our conversation, Kurt Vonnegut called me back.

"I thought that was a good interview," he said.

I agreed.

"And I think I have a title for it."

I asked him what it was.

"I AM THE FATHER OF ANNA NICOLE SMITH'S BABY!"

"I knew it!" I said.

"Use that, would you?"

Mr. Vonnegut claimed he was tired of writing, but he was still interested in getting a reader's attention.

During our interview, Mr. Vonnegut talked about growing up in Indianapolis, and some of the people that made a difference in his life.

KV: My special situation was that I was the son and grandson of architects. And so I saw building. We were building the city, and that was exciting. The thing my father was proudest of was the Ayres clock at the intersection of Washington St. and Meridian. That made him so happy. Ayres complained because he wouldn't send them a bill. There was stuff my family had done there -- particularly my father and grandfather -- that was quite permanent and wonderful.

NUVO: That clock is still an icon today.

KV: See, it was our city because we were building it. That's how I felt when I walked around town.

NUVO: It must have been amazing to be a kid and feel so engaged with the life of your city.

KV: Well, there was stuff going on, heroic events. One was what used to be, and probably still is, the largest moving project in history. The headquarters of the Bell Telephone Company used to be brick. What they did was take the old brick building -- with the operators in there saying, "Number please" and all that -- and they put it through a quarter of a turn and moved it half a block!

Then they built the new headquarters, which my father designed. So, yeah, there was stuff going on and my family was doing it. That was a very special situation.

NUVO: How would you characterize the politics and values you grew up with?

KV: We were German-Americans in a British colony, so we were outsiders. My ancestors came over from Germany about the time of the Civil War and one of them lost a leg and went back to Germany.

But they were all Freethinkers, formerly Catholics. It was science and Darwin, in particular, that made them decide, as educated people, which they were, that the priest, nice as he was, didn't know what he was talking about.

They were Freethinkers -- and that's what I am, except we're called secular humanists now. People stopped calling themselves Freethinkers because it was so specifically German and anything German was terribly unpopular because of the two world wars. My family became Unitarians instead -- it's the same sort of thing.

NUVO: Didn't Freethinkers place a great emphasis on rationality in public life?

KV: What we secular humanists do now -- and I am honorary president of the American Humanists Association -- like the Freethinkers, is try to behave as well as possible without any expectation of reward or punishment in an afterlife, and to serve as best we can, the only abstraction with which we have any real familiarity, which is our community.

NUVO: In your essay about being a native Midwesterner, you make a lovely connection with the Great Lakes.

KV: There's almost nothing like them anywhere else in the world, except in Asia. They're miracles all in themselves. In the middle of Siberia I guess there's a lake that big, but there are practically no other lakes that big with fresh water.

We are continental and the other people are oceanic. We have no ocean, but we look around and for miles and miles and miles there's all this land. Holy shit.

I'm so sorry -- we had this cottage up in Lake Maxinkuckee, in Culver. I've thought so often of the poor Pottawattomies we took this land away from. They must have loved it so.

One thing in the Middlewest: if you're in my business you're aware of the low opinion both coasts have of the midlands. And that is quite mistaken. New York would be a Kokomo if it weren't for Middlewesterners coming there.

NUVO: What accounts for the persistence of that low opinion?

KV: People like to feel entitled, whether they're actually entitled or not. They want to feel superior, so they imagine we're Bible thumpers and uneducated and all that. We used to have superb public schools. I guess we don't anymore, but, boy, the public schools were really something and I am a product of those in Indianapolis.

NUVO: What made Shortridge High School such a great experience for you?

KV: Learning. The people who taught really knew their stuff. My chemistry teacher, Frank Wade, was actually a chemist. I was so lucky in a number of ways. One of them was to go to school during the Great Depression because teaching became a plum job. The smartest people in Indianapolis became teachers. And, for once, there was something for women to do because teaching was regarded as a woman's profession, like nursing. So the smartest women in town -- Jesus, my women teachers were so exciting. My ancient history teacher, Millie Lloyd, should have worn a medal for her performance at the battle of Thermopylae. She was excited and we were excited.

Our classes were relatively small. Those small classes can feel like family. After a class in French or chemistry or whatever, we'd be talking in the halls about what we just learned.

NUVO: That's the way it's supposed to be.

KV: Yes. But it's too expensive and it would cut down on executive compensation.

NUVO: What was it like, being a teenager and having the chance at school to put out a daily newspaper?

KV: This had been going on at Shortridge since 1906. My parents had also worked on the Shortridge Daily Echo. The way it came into being was that when they built Shortridge High School, they had a vocational department and they had a print shop. Somebody realized, hey, students are printing dummy ads and dummy news stories, why don't they really print something. So there was the Shortridge Daily Echo, and a hell of a lot of writers have come out of Shortridge on that account. The head writer of the I Love Lucy show, Madelyn Pugh, was a schoolmate of mine. Dan Wakefield. Writing was a perfectly reasonable thing to do.

But also, this was an elitist high school. In a way it was a scandal because you could go there no matter where you lived, if you could get there. It was for over-achievers. It was for people who were going to college. So we were very special and we were hated for being ritzy.

NUVO: Who were the local heroes in those days?

KV: In those days great teachers at Shortridge were celebrities. I would look up to them. And we were into the Speedway. We'd take a train out to the Speedway where farmers had flatbed trucks with bleachers on them. They'd park in the infield and we'd sit on those. Our heroes weren't the drivers, they were the pit crews. That's because we were local, and we knew what was going on.

But you know who was a hero? Franklin Roosevelt.

NUVO: Wasn't Roosevelt a controversial figure in those days?

KV: Social class means a hell of a lot and upper class people -- no matter how well Roosevelt did -- it was stylish to hate him. What he did, which really offended them, was he strengthened the labor unions -- made it possible for them to strike. The oligarchs were furious because the working class was not supposed to have any power at all.

NUVO: Indianapolis has a fraught history with labor unions.

KV: I've written about Powers Hapgood. He was a Harvard graduate, son of a wealthy family who owned a cannery out there. After leaving Harvard, he went to work in coalmines and then was a CIO executive when I met him there, in Indianapolis. He had just come from court because there was some kind of dust-up on a picket line. The judge was so curious about him -- coming from a rich family -- why he would choose to live as he had. I guess you know what his answer was ...

NUVO: ... the Sermon on the Mount ...

KV: "The Sermon on the Mount, sir." That's important. And what I've said about the Sermon on the Mount is I'd just as soon be a rattlesnake if it weren't for the Sermon on the Mount.

NUVO: How did you happen to go crow shooting at Crown Hill Cemetery?

KV: Well, we were all gun nuts and they were called varmints, crows were, because they ate grain and so did we. American Rifleman and Field & Stream had ads for "varmint guns." Another varmint was a ground hog because a horse would be going along and he'd stick his foot in a ground hog hole and break his leg. So we were trying to prevent that, too. But we finally scared ourselves. We didn't realize we were nuts. My definition of a man's man is a man who knows gun safety, and we all did.

NUVO: Was there still an awareness or presence of the Ku Klux Klan in Indianapolis?

KV: It was headquartered in Michigan City, a long way off. I never saw them march; I don't think they did. As a matter of social class they would have been regarded as white trash. So I wasn't aware of that as I was aware of the widespread assumption that African-Americans were dumber than white people. I think my father believed that. I think everybody white did. You know, the Emancipation Proclamation was like giving freedom to domestic animals.

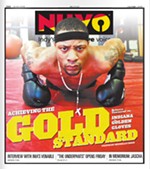

One of the things I'm going to say out there is how grateful I am -- and how grateful the world is -- for the tremendous gift of the Black people, of jazz. Wow. I don't know what anybody else in the world would want to thank America for, but man, it works. What I like about it -- and what public health people ought to like about it -- it's safe sex.

NUVO: Was the city completely segregated in those days?

KV: Yes. The Circle Theatre, Black people had to sit in the balcony. Any theater with a balcony, Black people had to sit up there. Black people couldn't check into any hotel except their own. And Black people couldn't eat anywhere except in their own restaurants.

NUVO: Were you aware of the local jazz scene?

KV: Look, it saved my life during the Great Depression. Hell, I was low and not all that happy in high school socially. My family was very depressed because they'd lost their money in the Crash. I didn't know what the hell to do and then I went to a place called The Southern Barbeque, which was on Meridian and, man, they were making jazz and they were so fucking happy when everybody else was so unhappy. I said, "This is for me!" For years thereafter, jazz kept me going. But also radio comedians.

NUVO: Who were your favorites?

KV: Jack Benny, Fred Allen. Their jokes were wonderful. It takes skill to be funny. The timing of Jack Benny was so fine. It is a form of genius for which we should be grateful.

I learned how to make jokes because I wanted to give people as much fun as they did, and I guess I did, too.

NUVO: Did you see much live performance?

KV: The bandleaders could be quite comical. Cab Calloway, for instance, at the Indiana Roof. Man, he was funny. That's what you do during hard times, you laugh your fucking head off. That's what we should be doing now, during the apocalypse.

NUVO: What about Indianapolis stays with you?

KV: People who were so good. There were angels.