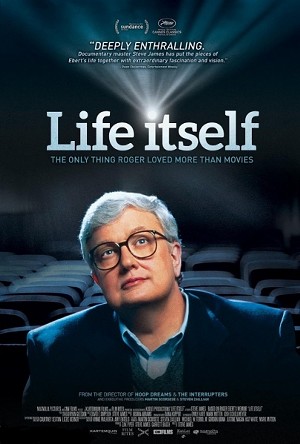

Documentarian Steve James — the filmmaker responsible for “Hoop Dreams,” one of the 20th century’s most significant additions to the genre — arrived at his lauded film-critic subject both too early and late to properly tell the story of a man whose prickly personality remains guarded. The film is based in part on Ebert’s 2011 autobiography “Life Itself” (not the most engaging autobiography ever written — “I was born inside the movie of my life. The visuals were before me, the audio surrounded me, the plot unfolded inevitably but not necessarily.”).

James had a running start at telling the life-story of a man who is disproportionately credited with putting a populist face on film criticism behind the likes of Pauline Kael, Gene Shalit, and Rex Reed. It is notable that Shalit and Reed were both years ahead of Ebert in terms of their presence on American television in doing exactly what Roger Ebert is give credit for accomplishing — namely giving an everyman’s editorial context about movies to a widespread audience.

James wisely abandons the guiding structure of the autobiography in an effort to present Roger Ebert’s cultural contribution in correlation to the way Ebert dealt with his painful terminal condition during his dying days.

Beyond its obligatory stream of talking-head interview segments with filmmakers, friends, and fellow critics, a good 30% of the film is spent with Ebert after his lower jaw had been removed — the result of his 2006 thyroid cancer surgery that left him unable to speak or eat. He had to use a laptop computer to serve as his voice (think Stephen Hawking). The reality of Ebert’s diminished state nauseates, and draws into question exactly why the ego-fuelled critic sought to extend his career beyond his own physical limitations. Roger Ebert had already won a Pulitzer Prize back in 1975 — an honor that would signify a career high for anyone else. Only four other film critics have won the coveted award since — not that the Pulitzer is any different from any other award; read hollow.

At one point in the film, Werner Herzog champions Ebert as a “soldier of cinema who cannot even speak anymore and yet he plows on.” Sadly, Herzog, like many of Ebert’s fans, misses the point of a career set upon by vultures. Watching the shell of a man being paraded around to give his signature two-thumbs-up to cameras and fans leaves a bad taste. Couldn’t he have spent his dying days sitting on a beach watching the ebb and flow of the ocean? No, no he could not. Why not? A love of film is one thing, but for a film called “Life Itself,” it raises a question about where the waning days Roger Ebert’s “life” got spent. No information is given about the web series he put together using other critics or about his legal battles over his show (“At the Movies”).

The documentary has already incited a predictable kneejerk round of adulation among critics, but it — much like the stomach-turning continuation of

RogerEbert.com past the man’s death — is not all that it is cracked up to be.

Henry Miller put the condition of an aging successful writer into succinct perspective in his book “On Turning Eighty.” “Success, from the worldly standpoint, is like the plague for a writer who still has something to say. Now, when he should be enjoying a little leisure, he finds himself more occupied than ever. Now he is the victim of his fans and well-wishers, of all those who desire to exploit his name. Now it is a different kind of struggle that one has to wage. The problem now is how to keep free, how to do only what one wants.”

Exploiting Roger Ebert’s name seems to be high on the list for a number of people’s priorities. At a time when Roger Ebert should have been taking life easy — he spent much of his last three years in the hospital — he felt pressured to keep on reviewing films, or at least to keep up the illusion of reviewing films. During his final years, his reviews were farmed out to a group of critics only too happy to be writing under the Ebert byline.

Roger Ebert was so ill during the making of the documentary that he was unable even to write even brief responses to questions that Steve James emailed him — softball questions about such things as his thoughts on the future of cinema. Herein lies the problem with the movie; it doesn’t much build on the autobiography from which it takes its name, nor does it give resonance to the nature of Ebert’s critical insights and editorial voice — which ran the gambit from essay to song-form in structure. It also doesn’t address the noticeable decline in his ability to write.

Instead we get gratuitous clues. Before meeting his wife at the late age of 50, Roger preferred prostitutes to pursuing romantic relationships. He was an alcoholic who turned to AA to break his addiction. An interview with one of his hookers could have gone a long way toward shedding light on his emotional state when he was at the height of his game. And what of the AA meetings he must have attending thousands of? What were his thoughts on alcoholism?

Roger Ebert was a film critic in the right place at the right time. Pauline Kael was far more deserving than he was to be the first film critic chosen to ever win a Pulitzer Prize — something Ebert was quick to lord over anyone in striking distance, namely Gene Siskel, whose bitey relationship with Ebert is exposed in the film. To his credit, James includes the notoriously web-famous outtake clips of Ebert senselessly berating Siskel during the filming of episodes of their series. Critic A.O. Scott designates Roger Ebert as “the definitive mainstream film critic,” but what of Gene Siskel, without whom Roger Ebert would have been just another critic for a daily newspaper; surely Siskel should get some credit too.

Before his cancerous physical condition took hold, Roger Ebert was a contentious individual with a chip in his shoulder. As Gene Siskel’s wife tells it, Ebert stole a taxi from her when she was eight-months pregnant. If you’ve never seen the clips of Ebert attempting to bully and humiliate Gene Siskel, you’re in for a shock.

The elephant in the room of Steve James’s boundary-crossing documentary is Roger Ebert’s wife Chaz — a former trial attorney — to whom many of his books are dedicated. By the end, the movie is as much about Chaz as it is about Roger. At the time of this review, Chaz — a woman who tirelessly supported her husband through the toughest of times — is doing press to promote the film.

Variety quotes Chaz as speculating that Ebert would have given “Life Itself” his trademarked “Two Thumbs Up” award of approval. On June 26, 2014, Indiewire posted an article with ridiculous lede “The Most Wonderful Things Chaz Ebert Said About Roger Ebert at a ‘Life Itself’ Screening.” Chaz’s quotes are prefaced with thinks like, “She’s thankful that Roger’s last review was of a Malick film rather than of Transformers,” “Chaz and Roger started communicating telepathically towards the end,” and “Chaz loved watching Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert fight.” Cough.

In full disclosure, I have been a longtime fan of Roger Ebert’s writing, television series (although I preferred Gene’s delivery and opinions over Roger’s), and books — I own no fewer than nine of them. I met Roger and his wife in Cannes in 2005. They sat behind me in a tiny screening room for a showing of Shane Black’s “Kiss Kiss Bang Bang.” Like many fans, I worried over his decline, and mourned his passing. Still, I don’t find much satisfaction in “Life Itself” as a documentary about a man and film critic for whom I hold much respect.

The movie spends too much time on the post-cancer Roger without addressing questions regarding his thoughts on cinema that the filmmaker acknowledges that Roger Ebert was too sick to answer. The movie doesn’t explain Roger’s plans to keep his website going after his passing. Most significantly, it doesn’t give the viewer a sense of the beauty of his writing. It’s one thing to say this is the most popular film critic in the world, but quite another thing to reveal the art in his craft. You couldn’t have a documentary about Mark Twain without getting at the voice in his writing or the variety in his approach. In the end, “Life Itself” has too much to do with Roger Ebert’s death than with the man who trademarked a couple of thumbs pointed either up or down.

Roger Ebert passed away at the age of 70 on April 4, 2013.

Rated R. 115 mins. (C-) (Two Stars – out of five/no halves)

-30-